Up to the beginning of 2021, many in the public associated cryptocurrency with crime and the quasi-legal fringe: the Silk Road drug market, ransomware attacks, sketchy investments. Computer nerds playing with fake money. That started to change last February, when Elon Musk announced his investment of $1.5 billion in Bitcoin. To some, this still just seemed like video game money, but the following month the record-breaking $69 million Beeple sale at Christie's became worldwide news. Since then a large swath of the art world has engaged with NFTs and crypto from artists to galleries to publications to museums, giving cryptocurrency legitimacy and a sense of cultural sophistication. Crypto traders who were previously identified as traders or speculators could now designate themselves as curators and collectors with NFTs. There's a significant amount of money and power involved, so I wanted to take a closer look at some of the potential problems with this technology that the art world and others are backing. Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology are at the core of all these related concepts like NFTs, Web3, and DAOs. Both the art world and the software world have divided opinions about crypto, but most people agree that blockchain technology is very effective for marketing. Blockchain explanations read like science fiction actualized, and they're compelling and understandable on a high level even without a lot of technical knowledge. Its capabilities convey a sense of intricate unbreakable security, redundancy, and community action.

However while the claims about blockchain technology's fundamental operation are generally true, the actual marketing and statements by its proponents often conflate different contexts, so that it's no longer quite accurate. And once a person has taken the time to try to understand the blockchain, cryptocurrency, NFTs, and who Beeple is, it's easy to miss some potential technical problems and political implications hidden within so much information overload. Some of the marketing is quite aggressive too, like how "Web3" falsely conveys the idea that it arrived from some consensus in the larger software industry when it's primarily just a marketing term from the crypto industry.

In this essay, I break down various claims and practical functions of crypto and NFTs, and examine some of the issues that concern NFT skeptics.

Art Authentication and Decentralization

Suppose somebody downloads an artist's work off their website and sells forged NFTs. Then later, the artist makes and sells legitimate versions of those NFTs. Using only the blockchain, how do you know which one is authentic? The blockchain in fact cannot know whether any NFT is a forgery without referring to some outside trusted service that has authenticated the artworks and identity of the artist. This is often referred to as the oracle problem. Artwork is plagiarized and sold as NFTs all the time, and authenticity disputes have arisen over CryptoPunks and over the original NFT created at Rhizome 7x7 in 2014, for which Kevin McCoy is now being sued. Because of these kinds of failures surrounding the indisputable provenance that proponents of NFTs allege they provide, artists are starting to realize the need for centralized services that properly and consistently validate artists and artworks, and that these services are not just conveniences but integral components of the system. Additionally, without a separate centralized authentication layer on top of the blockchain, there's no mechanism to solve problems like invalidating NFTs in the case of hacked artist accounts, or officially designating reissued NFTs in the case of theft or faulty minting. As you add this centralized authentication layer that's arguably doing a lot of the heavy lifting, then the decentralized nature of the blockchain starts to become less significant. It brings into question whether one could do art authentication in a more simple and robust way without involving the additional complexity and problems of the blockchain at all.

Some would suggest that it might be possible to achieve fully decentralized art authentication with some kind of code-driven policy that uses voting systems to authenticate art. But what about when 4chan hacks the system, or when they brigade the voting to get their counterfeit accounts declared legitimate? Once a decentralized system has all these problems worked out and integrates the requisite specialized human expertise, it's almost certain to arrive at the same structure you'd expect of a normal centralized art authentication service. Not everything is solved efficiently by software and voting, as anyone who has used moderation bots can attest.

Others say that smart contracts are the key to the true utility of the blockchain and NFTs. These scripts running on the blockchain provide basic programming functionality. However, NFT enthusiasts often underestimate the scope of the oracle problem, not realizing that the oracle's drive toward centralization runs through every aspect of maintenance, legal language, enforcement of terms of service, etc. A system of smart contracts could theoretically be created with strong administrative roles that can effectively reverse transactions in some cases based on terms of service, solving some of crypto's serious customer service and security issues. But if the contract requires an administrator to enforce a terms of service and operate the platform, then how can it be transferred to other NFT platforms? Protocols could be engineered into the smart contracts and legal language that allow the administrative role to be transferred to other platforms. But at that point it's just a full reproduction of traditional centralized databases on top of blockchain, and the blockchain part of the equation becomes superfluous and inefficient. Many NFT platforms fail to fully understand and address these and other oracle-related issues in their contracts, legal disclaimers, and tech designs, resulting in legal gray zones and ambiguity about pronenance that can bring lawsuits like those mentioned above.

The Sale of Digital Art

It's a common misconception that NFTs solve some technical or legal problem to enable the selling of digital art, but it's really intellectual property law that allows someone to sell art editions with certificates. In addition to artists like Cory Arcangel, Petra Cortright, and JODI who have sold digital editions with traditional certificates for many years, Rafaël Rozendaal and Miltos Manetas have been selling digital art on websites using ICANN's domain name system as an art registry since the early 2000s. And like NFTs, many of these artists’ editions are available to view online and do not depend on artificial scarcity.

But NFTs also introduce a new problem, which is that everything is public record and some of the most dedicated and thoughtful art collectors are very private. Even if a collector uses an alias, in many cases it would be easy to eventually figure out who they are by examining ownership records. To better mask a collector's identity, it would be necessary to tie different wallets to each NFT purchase, which can be cumbersome. And this still doesn't hide information like transactions and prices that collectors and artists sometimes understandably prefer to be private.

It's also worth noting that the often-discussed ability of NFTs to provide artist resale royalties is possible with traditional contracts too. However, in my experience selling digital and physical art for sixteen years, I've only seen one artwork that's actually changed hands. This would have resulted in a relatively small payout for that one artist had I implemented those types of contracts. Artists can really only make resale money in the near term if work is flipped frequently, which is not easily achievable or generally desirable, since the artwork is likely to end up in a random collection of speculative assets. And even in the long term, often only artists who are already successful truly benefit from resale royalties because they're the only ones who have significant second market sales with high enough prices for royalties to make a difference. I'm not against resale royalties, but think they're overstated as a reliable solution to support artists.

Storage and Digital Art Conservation

People often mistakenly think that the blockchain is able to store an artwork's media files in addition to the ownership registry, but this is not practical because it's extremely cost prohibitive unless the data is very small. Some artists do make artworks with a tiny amount of source data stored directly on the blockchain, but the vast majority of NFTs only contain a link to the artwork media, which is stored elsewhere. NFT media links typically either point to traditional web hosts, or they use the decentralized IPFS network, which has similarities to BitTorrent's file distribution system. However a significant disadvantage of traditional web storage is that there's no established way to fully validate the NFT's hosted data. What if a domain expires and is purchased by someone else? IPFS solves this problem by referencing files with a hash, which is a unique signature derived from the contents of the file. This does make it possible to validate the file's contents using the NFT's metadata, but methods to issue updates for artwork data using IPFS or on-chain data are not widely supported, and many digital artworks need to be updated over time to support new browsers and displays. Then again, for any serious professional art registry, the data should also be backed up on other platforms and offline, so neither IPFS nor traditional web hosting are a complete solution by themselves.

Another problem for conservation is the blockchain itself. The timescale of art ownership and digital conservation is long, and it's uncertain that any particular blockchain or storage system will still be operational in a few decades. Blockchain data will probably be migrated and archived somehow, but it's unpredictable if there will still be a running blockchain that's accessible as before with the same software. At best, the blockchain certificate will require ongoing maintenance to maintain access and functionality. Part of the reason blockchains may need to be preserved or emulated is for cases where the artwork interacts with the blockchain data. But more importantly, since the data on the blockchain is legally tied to ownership of the edition, the unknown lifespan of a blockchain introduces complicated questions about how the work may be sold far in the future and how blockchain preservation functions in a legal sense.

As absurd as it may sound in the NFT age, I still believe the best solution is archival paper certificates with a central database, because a good paper certificate can last over a century. Unlike Bored Apes Yacht Club theft victims who have no recourse to recover stolen work, I can simply invalidate the old certificate in my database and mail the collector a new one whenever a paper certificate is lost or stolen. If the certificate eventually disintegrates, then it can be replaced with digital documentation or some other placeholder. I've also considered using thin, engraved steel plates for longevity.

For many experienced digital art collectors who are buying for the long haul, a rapid digital art trading system just isn't that important, and none of the digital art collectors I work with have interest in NFTs. I plan to eventually pass off my database to an archive or to an organization that can maintain it long-term. But if that doesn't happen and I die, then all the collectors will still have the original maintenance-free physical certificates, records of purchase, and correspondence to prove ownership the old Antiques Roadshow way. If somebody someday brings a broken, decades-old laptop to Antiques Roadshow that's known to contain the key to a valuable NFT, there's actually some chance that an old photograph of the owner with their NFT and a copy of the current newspaper would be more useful for verification than the computer.

Compatibility with Museum Collections

Buying a movie on DVD doesn't mean you can publicly screen it, because copyright law reserves the right to public performance for the copyright holder. This is enforced strictly by the film and music industries. Consequently, digital artwork certificates should give explicit permission for public exhibition in order to be fully legally compatible with museum collections, because otherwise the museum might end up unable to exhibit a purchased work until copyright expires if the artist happens to be pedantic about copyright laws or just wants to prevent the work from being shown.

United States copyright law includes an exception to public display limitations if somebody actually owns a painting or sculpture. But that doesn't automatically apply to digital media, which makes sense, because it's especially useful for a digital artist to choose whether they are selling editions that are for private or public use. There might be some way a museum could win in a lawsuit about publicly displayed digital work if it comes to that, but the museum would be up against the longstanding precedent of the film industry enforcing public performance restrictions, so it's ideal to avoid that risk in the first place.

It's also typical for art certificates to include rights to use images of the work for promotion of exhibitions and the right to loan the work, and ideally NFT certificates should account for the obsolescence of the blockchain by specifying some way that ownership can be conferred if the blockchain no longer exists.

These potential incompatibilities with museum and long-term collections can probably be fixed by improving NFT certificates, and some platforms like Feral File and 1stDibs already get it right, but many others do not. The recent Andy Warhol and Refik Anadol NFTs sold by Christie's for $1-3 million specifically say that they are only for “personal” display, making them generally incompatible with museums. There are some generative digital collectible NFT projects like Bored Ape Yacht Club that almost confer full copyright, but that's a special situation made possible by the project's generative nature where each owner effectively has a diluted copyright that only covers a minor variation on a theme, and the project creators can still retain trademarks and copyright of some variations for themselves. But most artists are understandably not going to want to relinquish full rights of singular artworks because their work could then be used to market questionable products, or the owner could even stop the artist from using images of their own work.

Additionally, this all becomes moot once copyright expires, which is typically around one hundred years in the United States. A museum could probably legally download and archive millions of NFTs, store them until the copyright expires, and then exhibit the work freely after that. It would be interesting to peek into the future and see how the expiration of copyright affects the value of NFTs and other digital editions.

Artist Financial Support

A positive for some digital artists is that they're making significantly more money selling their digital work as NFTs rather than in the traditional art market. However the NFT market tends to amplify digital artists with large social media followings who were already commercially successful, or those who make work that fits well into crypto's narrow view of digital art. This leaves a lot of other digital art by the wayside. In Artnet's recent debut “ArtNFT” auction, which included historic digital artists like JODI, Vuk Ćosić, Claudia Hart, and Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, only about a third of the work sold, despite thousands of likes and hundreds of comments on their tweets promoting the auction. JODI's print at $800 (0.2 ETH) went without any bids, Ćosić's NFT print sold for $1000 (0.25 ETH), and Claudia Hart's NFT went unsold at $15,200 (3.8 ETH), and yet Kevin and Jennifer McCoy's NFT sold for $160,000 (40 ETH). The McCoys are talented artists who deserve success, but Kevin's status as the co-creator of one of the first NFTs obviously is playing into this auction's conspicuous price disparity and their other high dollar sales. Throughout this Artnet auction and the NFT marketplace in general, I frequently see signs that the NFT art market values a strong connection to crypto and NFT culture far above any deeper insight or connection to digital art history. (It should be noted that JODI was not involved with Artnet's auction.)

While on the topic of the Artnet auction, it's also worth pointing out this unprecedented situation in which publications of art criticism are also now auction houses for NFTs. Having an auction house integrated into a publication is a more severe conflict of interest compared to the advertising model, but that problem is multiplied by the fact that crypto and NFTs are extremely divisive. A substantial number of artists and writers see NFTs and crypto as problematic and don't want to be involved with businesses that sell crypto products, and now in some cases those people may have to decline opportunities for publication of their work.

Looking at how artist money is distributed in the NFT ecosystem, a recent study showed that only the top 1 percent of NFTs sell for more than $1000, whereas artists in the lower 34 percent of sales may actually be losing money on NFT sales because of fees. This suggests that NFTs are reinforcing or even amplifying the same kinds of disparities one finds in the traditional art market. Among digital artists that I follow, NFTs have worsened the revenue gap by a couple orders of magnitude between commercially successful digital artists and those who have minimal sales despite notable press and museum exhibitions. While some artists are able to gain significant financial support from NFTs without compromising their art practice, the system still leaves a lot of questions about equity, sustainability, and where the money ultimately came from if the bubble collapses.

Security

The blockchain database security system that drives cryptocurrencies and NFTs is generally secure, but a significant problem is the way blockchain security is marketed and deployed, which creates a sense of overconfidence with developers and users. Last year, there were billions of dollars in digital assets stolen and nearly two crypto thefts per month totaling over $10 million each. Developers and users who are relatively inexperienced with security rely too much on the blockchain without realizing that there are many layers and facets of security.

Multiple people have been tortured in their homes by criminals for access to their cryptocurrency. Previously there generally wasn't a good method to force a wealthy person to instantly transfer millions of dollars internationally in a way that's almost impossible to trace or reverse, but that is now possible with crypto coin shuffling services and other obfuscation techniques. Once crypto gets its act together in terms of security and consumer protection, those frictionless payments won't be quite as frictionless anymore, and the blockchain will only be one of many parts of the entire security system.

The Environment

The severity of crypto’s energy usage problem is a complex topic, and varies between blockchains. But something concerning about the larger crypto community is that I do not see much evidence of concern for the environment in general. There's a lot of misleading information about energy coming from the crypto industry, and even though improvements in energy usage could be made, progress seems to be overpowered by financial interest or convenience. You can see this in the slow move from power-consuming proof-of-work blockchains to more efficient proof-of-stake blockchains.

Another example of this pattern is how proof-of-work NFT marketplaces could have saved a massive amount of energy and artists' money just by allowing artwork to be listed for sale without minting it on the blockchain (“lazy minting”). Implementation is relatively straightforward and simple, and there's no reason lazy minting couldn't have been offered since initial launch. As a software developer, I can't imagine designing an NFT software auction system without trying to mitigate this kind of high-energy-usage problem from the start. I see people requesting this feature from NFT platforms on social media, but they don't typically get a response. As a result, many artists now unnecessarily have a significant amount of gas money tied up in crypto that they are not likely to get back, and I regularly come across forum posts by artists who are desperate to figure out how to sell and recoup their costs.

Even though NFT art enthusiasts and skeptics generally agree that only a tiny percentage of the incoming flood of NFTs are interesting or culturally relevant, the NFT ecosystem still expends a massive amount of energy to keep provenance records on all these NFTs that have no real value. And that's the killer feature that makes it appealing to speculators: that every NFT allegedly has its provenance tracked like a great work of art and could be worth a lot of money. NFT artists typically weigh their energy usage responsibility based on their own personal usage, but it's only a small percentage of NFT artists who actually benefit financially from the system. An alternate perspective that's also valid is to consider energy usage responsibility in terms of who benefits rather than who's suckered into paying minting fees. From that view, it's arguably a small percentage of NFT artists who are responsible for a very substantial amount of energy usage.

Financial Deregulation

Video games, banks, and quick pay services have been accomplishing digital transactions for decades without using blockchain technology. Second Life had an active economy of user-created digital items starting in the mid-2000s, and game economies had enough real world value that World of Warcraft gold-mining farm operations appeared in China. If all this happened before public blockchain technology was invented, then why is it needed? As a software application, the blockchain is just an append-only database with data integrity checks, and those features can be replicated more efficiently by traditional databases. More than ten years after crypto was invented it is still rarely used like actual currency, and many claims about the advantages of blockchains over traditional databases are vague or unfounded.

The key unique characteristic about blockchains compared to traditional databases is that they don't require a central authority. And while many computer scientists are highly skeptical of other practical applications of blockchain technology, it's clear that this lack of central authority has the massive effect of creating a liquid asset class that easily evades regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and other regulating entities. It's a new type of distributed, autonomous, international machine with no central authority or admin password, so it lies outside the bounds of current laws and creates challenges to applying laws even when they are enacted.

The SEC and FDIC were created in response to the crash of 1929 to avoid market manipulation, speculation, fraud, and other issues that led to events like the Great Depression. They try but do not always succeed at preventing disasters like Enron, the 2008 financial crisis, and Bernie Madoff. One of the most significant accomplishments of the Occupy movement was their 325 page letter to the FDIC containing recommendations of stricter banking regulations, which was cited dozens of times in the actual FDIC ruling for the Volcker Rule that prevented banks from making speculative investments.

Cryptocurrencies generally have the opposite effect, creating a financial market that's much more difficult for the SEC and other agencies to regulate. Even if you're a libertarian and a fully deregulated “buyer beware” financial market fits your politics, cryptocurrency still has problems for many usages since it doesn't fit the politics of other countries like China, where crypto is banned. Nine countries have now fully outlawed crypto, which accounts for more than 25 percent of worldwide internet users combined. This means that Web3 and NFTs are mostly off the table in those locations, or at least severely limited and unpredictable. Additionally, at least 42 other countries have enacted crippling regulations on cryptocurrencies.

Recent regulations on NFTs in China prohibit storing NFTs on a public blockchain, exchanging NFTs for cryptocurrency, or selling NFTs for profit, which are not compatible with the concept of a professional global art ownership registry if strictly enforced. It seems unlikely that the Chinese Government will loosen up the NFT market, considering that they've strictly banned cryptocurrencies, and any lightening of NFT regulations would allow collections of NFTs to be used as makeshift cryptocurrencies since they are almost functionally identical from the perspective of speculators. Some smaller companies in the Chinese NFT art industry were using Ethereum before the crypto ban, and some in the Chinese crypto industry are hopeful that regulations will be lifted. However analysts are skeptical that regulators will allow this to continue. Doing without China and other countries in the crypto space may be acceptable in the context of hyper-competitive business, but it's at odds with some of the idealistic notions being marketed around NFTs, Web3, and DAOs. A professional universal art registry whose core technology creates a barrier to inclusion of artists in China, Egypt, Iran, and other countries is a problem.

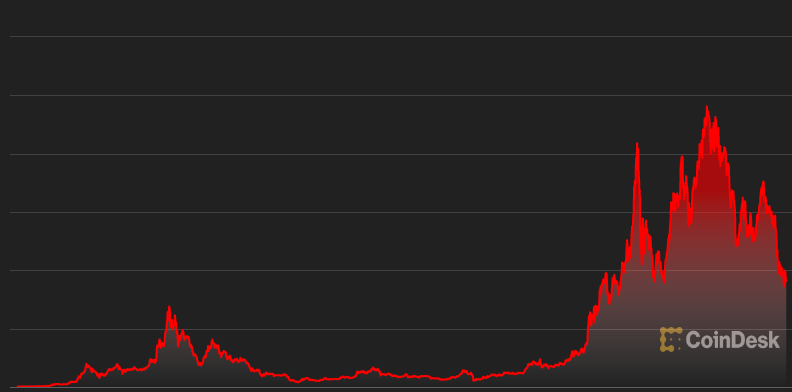

This new unregulated market of cryptocurrencies makes possible things like frictionless worldwide transfers (except China, etc.), one-minute loans, and anonymous creation of businesses, with the trade-off of high energy usage on average per transaction and a market with more fraud, pump-and-dump schemes, and evasion of gambling laws. But is crypto trading really gambling and some kind of Ponzi-like scheme or fraud? Can it be both? Cryptocurrency as a whole functions similarly to a Ponzi or pump-and-dump scheme where recruiting more people into the system and building hype makes it seem like everyone's making money while creating minimal value. Although a system like this is unprecedented in some ways and nobody really knows what will happen, the people investing are making the risky bet that something closely resembling a Ponzi scheme will have a different outcome.

Many reputable computer scientists think that public blockchain technology is not actually that useful. And there are strong indications that if major players cashed out, it would cause a crash and cash-out rush where only a relatively small percentage of investors would actually get compensated, leaving a lot of people holding an empty bag. Stablecoins like Tether, whose values are tied to the US dollar, account for more than 70 percent of bitcoin transactions, and it was originally claimed that Tethers were backed by actual US dollars. However a Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) investigation forced them to reveal that the majority of Tether is backed by what are essentially corporate IOUs for which they refuse to release any details, and 26 percent isn't backed at all. Additionally, unlike with banks, which are insured, a crypto exchange bankruptcy will likely consider the asset holder as a secondary creditor who may not get money back for years, if at all. There are also structural weaknesses, like how bitcoin miners can no longer cash out without crashing the market and are now using bitcoin as collateral for loans to pay energy bills, creating a potential house-of-cards situation if bitcoin falls below a certain price. This precarious and volatile system is now being marketed to everyday people through celebrities, public transit ads, and sports ads, and 64 percent of those investing in crypto last year used credit to do so. When a system like this crashes, it's not likely to be the casual investors who come out on top, and many crypto skeptics argue that this risk is one of the primary reasons to completely avoid participation.

Keep in mind that traditional art collecting frowns upon “flipping” artworks (selling after a short time of ownership) because ideally you want artworks to go to collectors who will live with the work, support artists' careers in the long term, and are building serious collections that may someday end up in museums or archives. However with NFTs, flipping is not only acceptable, but the frequency and prevalence of flipping in the NFT world is on a completely different level. And when you reduce friction, time-compress, and raise the stakes on art trading to a point where it will inevitably produce the same dopamine responses as something like sports betting, it's not really the same game anymore. Gary Gensler, the chairman of the SEC, agrees and has compared crypto schemes to unlicensed gambling: “We’ve got a lot of casinos here in the Wild West.”

Crypto's unregulated, borderless market also makes it conducive to crime. Crime in crypto is sometimes dismissed as a non-issue, but this is partly because the crypto industry has been providing somewhat misleading crime information. Many reports and articles about crime take data from the same few companies in the crypto industry, like Chainalysis. But looking at their actual report, the methods are primitive, and it states that the given crime rate should be considered a “lower bounds” since it's only based on crime they can identify without any real holistic analysis. A deeper academic crypto crime study from 2017 estimated total annual crime-related transactions at $76 billion, while Chainalysis reported only $8 billion that year. During the review process of this essay, multiple crypto-optimistic editors suggested this paragraph should be removed, and I was provided a 2021 report by an ex-CIA operative as justification for its removal. However, the report's telltale indications of crypto marketing led me to a Forbes article by David B. Black explaining the report's problems and revealing that it was in-fact covertly commissioned and funded by crypto companies. A thorough analysis of crime is beyond the scope of this essay, but crypto industry crime statistics should be taken with a grain of salt. Likely few artists or institutions have a direct cause-effect relationship with crime in the crypto world, but I think it's important to fully understand what the art world is engaging and legitimizing. The art world's involvement in crypto and NFTs may also attract hackers and theft, and the recent Outland Discord fraud incident is arguably an example of that.

The degree to which all these risks in crypto will lead to wider problems or economic disasters like 2008 depend on how big crypto gets and how well it can be regulated, but it's already huge and naturally resistant to regulation. The crypto system is also conducive to the invention of new ways to evade the SEC and other regulators, and crypto could potentially stay one step ahead of slow-moving government regulators indefinitely. The power of regulators may come down to legal battles over jurisdiction or coin shuffling services, which could be left up to the unpredictable Supreme Court to decide. Even if the crypto industry can be fully regulated, political bartering power may need to be spent to get it there, like the deregulation of traditional financial markets in exchange for more regulation of crypto. And recently the conservative divide within crypto has become more pronounced, with general involvement and decrying of regulations by Ted Cruz, Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis, Greg Abbott, Tucker Carlson, and Jordan Peterson. Liberals’ opinions are more mixed, and are generally aiming for stricter regulations or bans. But that may start to change with the crypto industry pouring money into Democratic primaries and sending an army of lobbyists to Washington.

Art's Relationship to Crypto

The crypto industry is ridiculously complex, and it's not easy for an artist, curator, or institution to determine their true relationship within it and what larger effect that may have. I don't engage with NFTs, but I didn't write this essay to call out artists who have; I just wanted to share additional perspectives.

I see that artists and people in the art world are genuinely concerned about the energy usage issues and the hyper-commercialization of the NFT market, and many were initially wary of a market going from nothing to astounding prices and popularity overnight. But then people understandably came away with differing opinions about energy usage depending on which sources they read, and the subject of energy became a divisive issue that may have obscured some of the deeper problems with crypto and NFTs. A lot of the strongest and most vocal criticisms of crypto products are coming from software developers and economists, and I've noticed that this wider criticism has been somewhat isolated from the art community. I often see the claim that crypto skepticism is similar to concerns about the early internet, but I was a professional developer in the '90s, and what I saw was that the utility and game-changing potential of the internet were plainly obvious to all engineers in the industry. The concerns about extreme overinvestment in the dot-com bubble were not about the technology itself. This widespread backlash by mainstream software developers to a new technology like crypto and NFTs is unlike anything I've ever seen in the software industry.

Before NFTs, many digital artists were originally drawn to digital art specifically because it was free from the commercial motives of the art world, and a good number of those artists will probably never engage with NFTs even if blockchain authentication continues to be popular. Additionally, a large portion of digital art just doesn't fit well into the NFT market or format, and I've already noticed how the proliferation of NFTs is considerably narrowing the vision of what people even consider to be digital art. In many ways the term “NFT” has started to replace the term “digital art,” resulting in the exclusion of digital artists who choose not to engage with NFTs for ethical or practical reasons. But I also now am seeing exhibitions and articles that are simply framed in the context of “digital art” and its history where even without explicit framing around NFTs, only canonical artists who happen to engage with NFTs are included. And the other historical artists you'd expect to see in the same context are replaced with people like Tom Sachs, Jeff Koons, and other artists who don't have meaningful connections to digital art history and who likely hired somebody to help make NFTs based on illustrations. The Shadertoy graphics community is one of the most active and distinct predecessors to the generative NFT art scene where artists had already started making in-browser generative artworks as a community nearly a decade ago, which often closely resemble current NFT trends, but I've not seen them mentioned anywhere in the last year. I frequently see oversights like this, and I've noticed that for people trying to promote NFTs and their sales, there's a strong incentive to mention brand-name traditional artists and institutions because it makes NFTs seem innovative and game-changing. Yet there's a disincentive to talk about all the artists who were already making and selling digital art for decades since it can make NFTs seem less innovative, bringing into further question the value proposition of NFTs that already is widely questioned.

Many well-intentioned people in the NFT art community underestimate how much the speculative, pump-your-bags culture of crypto bleeds into all areas of NFTs and digital art, creating a very poor filter for which digital artists actually get attention. The art in most NFTs is simply an image or video, and even the most elaborate NFTs are still generally just JavaScript or some other specialized language talking to a database API. Net art has been investigating wider cultural phenomena through online software and databases for decades, and this should be a big moment for all digital artists regardless of what type of certificate or database they happen to use. I hope curators and writers will continue to remind people that the artworks people currently associate with NFTs are only a hint of a multitude of interesting forms of digital and technological art that exist.

Further Reading

Artist Geraldine Juárez on NFT Ghosts:

https://the-crypto-syllabus.com/geraldine-juarez-on-nfts-ghosts/

Software developer Moxie on the problems with web3:

https://moxie.org/2022/01/07/web3-first-impressions.html

Artist Joanie Lemercier on the centralization of Nifty Gateway:

https://joanielemercier.com/null-and-void/

Slate article about the risks of Stablecoins:

https://slate.com/technology/2021/10/tether-crypto-danger-ben-mckenzie.html

Writer Stephanie Glen on the problems with smart contracts:

https://www.datasciencecentral.com/theres-trouble-brewing-with-smart-contracts/

Artist Martin O'Leary on the case against crypto:

https://www.watershed.co.uk/studio/news/2021/12/03/case-against-crypto

Software developer Molly White on considering the harm of technology:

https://blog.mollywhite.net/abuse-and-harassment-on-the-blockchain/

Software developer Molly White on how it's not still the "early days" of web3:

https://blog.mollywhite.net/its-not-still-the-early-days/

Artist Everest Pipkin on energy usage and other issues in cryptoart:

https://everestpipkin.medium.com/but-the-environmental-issues-with-cryptoart-1128ef72e6a3

Writer Jesse Frederik on why blockchain technology is mostly useless:

https://thecorrespondent.com/655/blockchain-the-amazing-solution-for-almost-nothing

Artist Kimberly Parker on how very few artists are making money off NFTs:

https://thatkimparker.medium.com/most-artists-are-not-making-money-off-nfts-and-here-are-some-graphs-to-prove-it-c65718d4a1b8

Artist Joshua Caleb Weibley on some of NFT's legal issues and relationships to art history:

https://www.x-traonline.org/online/a-non-fungible-treatise

Engineer David Rosenthal on the problems with cryptocurrencies:

https://blog.dshr.org/2022/02/ee380-talk.html

Artist Brad Troemel's NFT Report on various issues with NFTs (video):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXBxVFsHBJQ

Writer/YouTuber Dan Olson's deep dive on the problems with NFTs and crypto (video):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQ_xWvX1n9g

Artist and developer Marin Petrov on the problems with DAOs:

https://world.hey.com/marin/daos-and-the-nature-of-human-collaboration-be162918

Writer and tech theorist Tante on the problems with web3:

https://tante.cc/2021/12/17/the-third-web/

Jacobin Magazine deep dive on the problems with crypto:

https://jacobinmag.com/2022/01/cryptocurrency-scam-blockchain-bitcoin-economy-decentralization

Writer David Gerard on how Bitcoin miners can no longer cash out without crashing the price:

https://davidgerard.co.uk/blockchain/2022/01/22/bitcoin-goes-down-and-time-bombs-are-waiting-in-the-market/

Reuters article on the problematic history of Tezos:

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/bitcoin-funding-tezos/

Cryptopedia on the problematic history of Ethereum and The DAO:

https://www.gemini.com/cryptopedia/the-dao-hack-makerdao